Calvin Tsao and his brother Frederick are American, but they were both drawn to China from an early age. “Even though we’re immigrants, our parents had us steeped in Chinese culture,” says Calvin Tsao. After growing up in California, he made his way across the Pacific to work on I.M. Pei’s groundbreaking Suzhou Museum, the first foreign-designed project in a country that had just opened up after decades of isolation. His brother began to establish business links with the country of their ancestors.

Tsao eventually returned to the United States, where he founded an architecture firm, Tsao & McKown, with partner Zack McKown. Meanwhile, China transformed itself from one of the world’s poorest countries into one of its most powerful, but Tsao saw something was amiss. “I have a long view, having experienced the evolution of China over the last 30 years,” he says. “And while its economic and political presence and authority in the world is in ascent, their attention to social health has been spotty.”

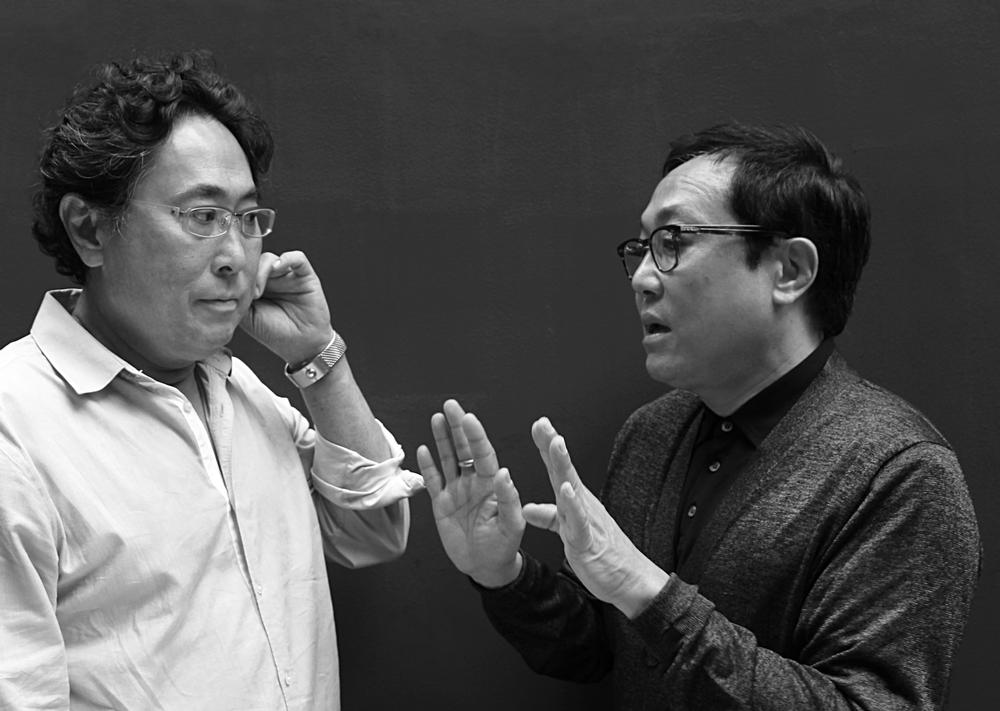

Tsao was particularly alarmed that China seemed to have lost touch with some of the spiritual and cultural anchors that have held Chinese civilisation firm for centuries. One night, he and McKown pitched Frederick Tsao an idea: start a new company that would develop properties centred around cultural, physical and mental wellbeing. “My brother is an industrialist, he has a lot of resources, both political connections and financial strengths,” says Tsao. “We thought he could help. And indeed he took that idea to heart.”

GIVING BACK

The result is Octave Living, named for the interval between one musical pitch and another, as if to symbolise the switch from profit-focused development to something more enduring. “Can you make a sustainable endeavour that balances profit with giving back?” asks Tsao. “Octave is really about looking at economic models and seeing how we can do something that’s good for our society.”

Octave Living could provide a reference not only for Chinese development but for cities around the world, believes Tsao. Its message is straightforward: the key to a happy and successful society is not only more growth and more money, but a kind of personal and social equilibrium. It’s a philosophy to design and development that places wellness at the heart of everything.

With the help of Frederick Tsao, Tsao and McKown were able to launch Octave Living’s first project in 2016. The Living Room is a ‘holistic urban wellness centre’ located in a historic compound in Shanghai’s Former French Concession, a handsome district of streets lined by plane trees. Spanning 21,500 square feet, the centre includes space for early childhood development programmes, family therapy, art therapy, yoga, a restaurant and a small urban farm.

The architecture seems designed to soothe. Serenely minimal passages lead to spaces filled with natural materials like wood.

WELLNESS RESORT

The next project from Octave Living, which opened last year, is much larger and more ambitious. Sangha is a wellness resort located in Suzhou, a city west of Shanghai famous for its classical Chinese gardens.

Rising over one million square feet on the shores of Yangcheng Lake, the complex includes an event space, a chapel, educational facilities, a 75-room hotel, a spa, and a wellness centre with meditation rooms and a clinic that integrates Chinese and Western medicine. It’s a space not so much for a holiday as for a period of self-improvement. When guests check into the hotel, they’re given a medical exam and greeted by a personal wellness coach.

LIVING THE EXPERIENCE

It’s an experience that some will enjoy full-time. Sangha includes 109 single-family houses and 89 flats, whose construction were required by the local government. Tsao says he and his brother never wanted to include free-standing houses, since they find them unsustainable by nature, but they soon realised that the profits from selling the residential units would help fund the rest of Sangha’s programme.

And it’s the programme that led the design, not the other way around. “Living Room and Sangha have different proportions of programmes,” says Tsao. “But the gist of it is mind-body wellness, which means healthy mind, healthy body.” In terms of design, “it means capturing natural conditions like light, breeze and temperature in the man-made design,” he says. One example is the Living Room’s farm.

“When you look down from the higher buildings on the complex you see this greenery, which we use to produce ingredients for our eateries,” explains Tsao. A number of studies have shown that even a glimpse of greenery has important psychological benefits.

Another example is the way both Sangha and the Living Room deal with internal circulation. “We put in a lot of stairs and corridors and internal bridges that make you perceive the spaces both orthogonally and diagonally,” says Tsao. “You’re always changing your point of view. It addresses qualities of navigation and wayfinding – engaging your senses about where you’re going, where you’re coming from, what you see along the way.”

Tsao & McKown led the design for Sangha, but they also invited two other architects to take part: Yung Ho Chang of Beijing’s Atelier FCJZ and Lyndon Neri of Shanghai-based Neri & Hu. “We had an agreement that they had to conform to certain basics – grey, white and earth tones,” says Tsao. All materials are sustainable, in order to keep the project’s carbon footprint as low as possible. “We don’t use any quarried stone,” says Tsao by way of example.

The invited architects were allowed one special material of their own. Chang chose a kind of rough terrazzo that was popular in Shanghai in the 1930s. Neri chose a grey brick tile that evokes the kind of brick used in Suzhou's gardens. "There's a series of walls he designed called the sanctuary that creates shadows. It's very beautiful,” says Tsao.

THE BIGGER PICTURE

It all adds up to an eye-catching setting, but Tsao says aesthetics are only part of the picture. “The buildings are just containers for content,” he says. “And it’s the content in which the revenue will finally come.” In a country that has changed so quickly and so thoroughly, Tsao is banking on the need for a pause – and a new kind of architecture that encourages reflection, health and well-being. “We want to let people know that this can be done,” he says. “It’s a new way to develop our cities and our world.”