Juggling a busy global architectural practice in London with family life, South African Jennifer Beningfield finds balance on regular trips to her holiday home in the Great Karoo desert – one of the most ancient places on earth.

Called the Swartberg House, the property looks out over the wild desert, where mongoose, tortoise, hares and aardvark roam free. It’s a 24 journey from London and a four and a half hour drive from Cape Town, so the family blocks out time and goes for eight weeks each year.

The magic of the vast landscape and soaring backdrop of the Swartberg Mountains was central to the decision by Jennifer to buy the land – previously a remote sheep farm – and to build a family home there.

“It’s important for people to be rooted in place,” she says. “This is a very special house, with powerful connections to nature and we go there to de-stress, to de-clutter and to tune in to the natural environment.”

Equal priorities on these precious visits are resting and recharging and spending time with friends and family, as Jennifer explains: “We lack time in London to connect with people over a period of a few days, just to be able to relax and be together. We often have guests while we’re in South Africa and that’s very special.

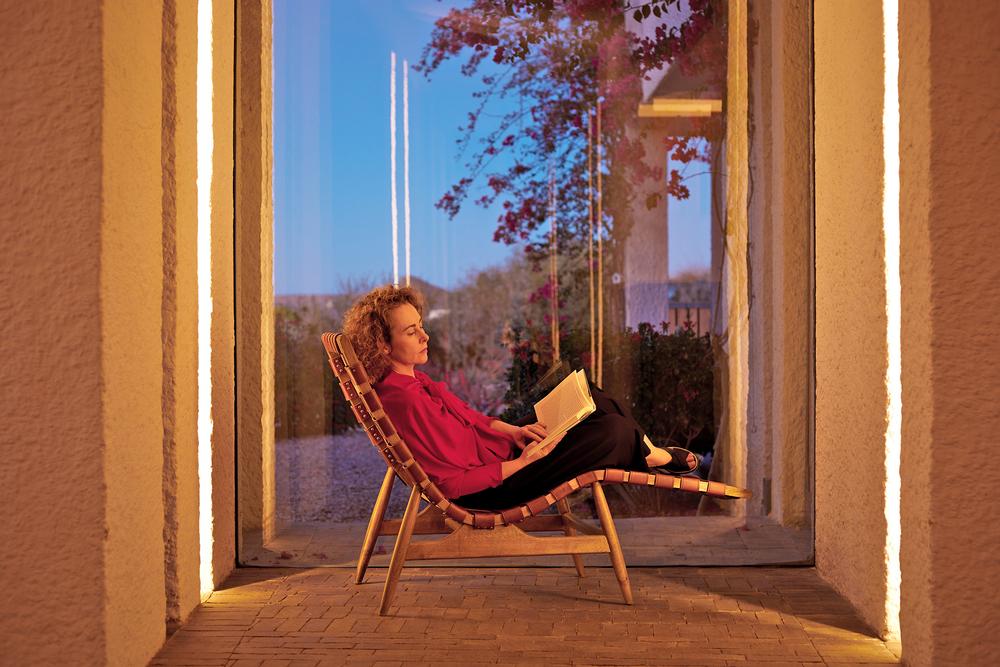

“The house has been designed with lots of spaces to retreat to, as well as spaces to socialise,” she says, “So it’s a place that really reaches out to people.”

Recharging is also a big part of the family’s time in Africa. A lap pool – an ‘oasis in the desert’ – is perfect for both daily exercise and cooling off in the heat, which can reach 40°C in summer, while a nearby yoga studio in the small town of Prince Albert offers regular classes.

The pool is enclosed by a stone wall which was chosen to match the colour of the mountains behind. It also recalls the dry stone enclosures which are used for livestock in the local area and is intended to provide a secluded world for contemplation by blocking out all distractions.

HIKING AND HORSE RIDING

“We get out into the environment,” says Jennifer. “There are beautiful walks. We climb and go hiking in the mountains, and our daughter loves to go horse riding.

“The garden is also very important. We wanted to use the landscaping to heal the land, as it had been over-farmed and needed to be regenerated.

“The new planting has been really successful,” she says with a smile. “It’s attracting lots of bees. We also created an orchard and have started to pick our first fruit – pomegranates, plums, peaches, figs, grapefruit, lemons, oranges and kumquats, and we enjoy this fresh-grown food.”

An outdoor seating snug is a focus for social time, with the area screened from the harsh west light in the summer and from the wind which blows on hot afternoons. A fire circle warms on cooler days and into the evenings.

SUSTAINABLE BUILDING

The location meant building sustainably was always going to be the best option, but Jennifer says it was also the right thing to do and a fundamental part of the philosophy of the project: “The house is very remote,” she says. “Being self-sufficient was an important part of the plan, so we created a solar house which is cooled by natural ventilation.”

A low-tech emphasis meant using ancient cooling methods to keep the house from overheating in the fierce summers.

The building has been designed to trap the cold desert air at night to avoid the use of air conditioning, as she explains: “The fabric of the house is the means by which we regulate the temperature inside. The ‘ventilation system’ is operated by us manually opening and closing huge shutters and doors in different parts of the house at different times of the day.

“We open the roof at night and let the cold night air fill the house – it’s a precious resource in the desert – and then we keep the cool night air trapped inside during the day.”

Half meter thick walls protect against the fierce sun and bitter cold and the huge extremes of temperature which can go from a blistering 40°C to minus -6°C between seasons.

In winter, the large windows act as sun-catchers, allowing the dark brick floors to radiate the stored warmth of the sun in the cool evenings. “I grew up in South Africa and understand the climate here well,” she says.

“To design this way, you have to know the angles of the sun and direction of the winds at different times of year and use these to create shade and to ventilate. We effectively made the building so it responds to the environment.”

RHYTHMS OF NATURE

This low-tech approach has other benefits in terms of life at the Swartberg House. “The technology is manual,” explains Jennifer, “We have to adjust the house ourselves throughout the day and be aware of the environment around us.

“This connects our body’s rhythms to the rhythms of nature – the house brings the two into harmony and so to live here, you need to stop and breathe and connect.

“While technology can be helpful, the consequences of relying on it as a society to heat and cool our buildings means we’re not taking responsibility for our actions,” she says. “In choosing this very manual cooling process, we’ve removed the separation which is caused by technology.”

The outcome is a more calm and mindful way of living. “This house is about embedding people in the world and connecting them to nature,” she says.

“The design also connects the building to the place,” she explains. “It was laid out to give views of the landscape, with the huge picture windows facing the mountains.”

PLAYING WITH LIGHT

Many people take a view of ‘the more the better’ when it comes to deciding on lighting sources in their homes, and many modern homes are extremely bright, but the Swartberg house takes a more subtle approach, with shadow and shade being valued just as much as brightness.

“Sometimes we roll back the shutters and open the huge windows and flood the house with light,” says Jennifer, “But at other times, we long for shade and a rest from the sun.”

The house has a series of small scattered openings, which allow shafts of light to penetrate into the shadows, and these have been carefully configured according to the positions of stars in constellations which are visible from the upper roof terraces.

At night, concealed LED strips integrated into both the external and internal openings illuminate the interior, while from outside, the house is lit with an irregular pattern that’s also in sympathy with the scattering of stars in the dark skies.

The series of large elevated roof terraces embrace an openness to the sky and are used as gathering places on warm summer evenings. They give far views of the mountains and bring people closer to the clear, star-filled skies.

“The Great Karoo has no light pollution,” says Jennifer. “The house is so remote and the humidity levels are so low that the air is clear and the night sky is dramatic – you can see the Milky Way without a telescope.

BUILDING FOR HEALTH

As an architect, Jennifer knew the health of the family would be defined by the quality of the building, so natural materials were used throughout the process and volatile organic compounds were eliminated from the construction.

The 230sq m house was created by local builders for less than £200k. It uses a limited number of robust materials, including brick floors made from local Western Cape clay.

Local crafts were also used – “The house is limewashed inside and outside on roughcast plaster – an ancient material which was applied by hand,” explains Jennifer.

“The house is organically stable, so we get good air quality,” she says, “And the external doors are all double glazed, which is unusual in South African domestic architecture.

“The only material which isn’t local is the wood. Due to sustainability certifications, we couldn’t get FSA certified timber locally, so we used American White Ash from the US.”

The house is ‘geometrically loose’ – not linear. “It bends and flexes to the landscape,” says Jennifer. “I like the idea of change in buildings – they should alter if people’s lives change, and not be so fixed that they inhibit the way they want to live.

“I believe in architecture that’s resolutely contemporary, but also feels ancient and timeless,” she says. “Timelessness is important – we need to find a balance, so the house still works for the people who live there in 200 years’ time.

“When I think about buildings, I imagine the lives which have been lived in them and appreciate how they have a resonance with a particular place and time. Viewing things this way opens up a world which is bigger than you.”

LONDON LIFE

Back in the real world, Jennifer is working on a wide range of projects, including a residential development at Westminster Fire Station in London. Her practice also recently won a RIBA competition to design new mass-market homes for Taylor Wimpey: “I told them they need to put joy into house building,” she says with a smile, “And they listened.

“The idea of generosity is very important to me,” she concludes. “We must design spaces which bring people joy.”

It seems that although the Swartberg House in South Africa is very much a one-off, the spirit which created it will touch and bring joy to many more lives in future years.